|

General Global Warming / Climate Change Discussion

|

|

| Fireinthehole- | Date: Sunday, 22.12.2013, 11:36 | Message # 91 |

Pioneer

Group: Translators

Sweden

Sweden

Messages: 365

Status: Offline

| Looks like there will be no snow this christmas and new year  I read that the town I grew up in has snowy christmases in 9 out of 10 years, where I live now has only 5 in 10, and the distance is only 100 km. I read that the town I grew up in has snowy christmases in 9 out of 10 years, where I live now has only 5 in 10, and the distance is only 100 km.

Love Space Engine!

|

| |

| |

| midtskogen | Date: Sunday, 22.12.2013, 16:37 | Message # 92 |

Star Engineer

Group: Users

Norway

Norway

Messages: 1674

Status: Offline

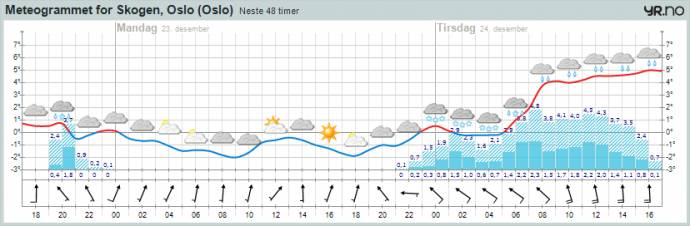

| Warm periods in December are pretty common in Scandinavia. Here in Norway there even is an old word for it, "kakelinne" (="Cake mildness", from the belief that the cause for the mild weather is all the cooking just done for Christmas). But this December has been extremely stormy. Only patches of snow left here and the short term forecast looks like this:

That's the most crappy Christmas weather I've ever seen here if it turns out like that, around 30mm of rain and sleet on Christmas eve (which is the day celebrated in Norway).

Is this more common when AMO peaks? I don't know.

NIL DIFFICILE VOLENTI

|

| |

| |

| Watsisname | Date: Sunday, 22.12.2013, 17:43 | Message # 93 |

Galaxy Architect

Group: Global Moderators

United States

United States

Messages: 2613

Status: Offline

| Quote midtskogen (  ) A study recently fixed the surface temperature hiatus by using satellite data to fill in missing areas, particularly the Arctic, usually missing in global temperature records.

The link between the Arctic and the Atlantic should be obvious, but this cycle, whether it's called AMO or Arctic, still seems relevant to the study. It should have dealt with the coincidence that last AMO turn and satellite era begins at the same time.

The AMO’s positive phase is correlated to warmer arctic temperatures (particularly sea surface temperature), and since the arctic is one of the largely undersampled regions this causes a cooling bias in the global temperature dataset. Arctic Amplification (ice-albedo feedback effect, in a nutshell) is also at play here.

The paper does not discuss these things because its motivation is to understand how the sampling regions and methods affect the production of a global temperature record. It is not interested in the mechanisms that cause these regional variations in the first place. (The authors are working on data analysis, not climate dynamics). The climate dynamics at play here is interesting and complex enough to warrant its own study, and indeed there have been a fair number of papers on the relation of AMO, arctic temperature, ENSO, and thermohaline circulation in the last few years.

The takeaway from this is that the global warming signal is more pronounced when we spatially extend the dataset to cover the whole planet, thus counting regions that are warming faster than the global average, e.g. Arctic, and the signal is also very clear when we factor in the effects of internal variability and non-greenhouse forcings.

|

| |

| |

| Watsisname | Date: Sunday, 22.12.2013, 17:53 | Message # 94 |

Galaxy Architect

Group: Global Moderators

United States

United States

Messages: 2613

Status: Offline

| Regarding winter, I got a number of good early-season snowfalls, but now it's been very warm (record warmth for DC area today actually).

No, this isn't global warming, but extreme jetstream configuration, advecting warm air from the gulf over the eastern US while the west US and plains are under a cold spell. This is opposite setup to earlier this month when it was very cold and snowy here while Alaska baked.

There is some research suggesting a link between arctic amplification and more extreme jet stream configurations; I'm not entirely convinced by it (too short of a time period of study), but it is fairly interesting and compelling.

|

| |

| |

| midtskogen | Date: Sunday, 22.12.2013, 19:31 | Message # 95 |

Star Engineer

Group: Users

Norway

Norway

Messages: 1674

Status: Offline

| The study, as long as it confines itself to 1979-, is fine. And it does, sort of, but care must be taken when making it relevant for the 20th century global warming trend, which even the authors go far in doing. If there is Arctic warming due to rising AMO, it means that the 1950-1980 global cooling has likely been underestimated, by the same argument.

Since the AMO and the Arctic link are local and are not caused by AGW, one should try to filter out their effects when identifying the GW trends. Undersampling in the Arctic may be one way to do that, although a bit crude.

The weather: The low pressure of the Christmas storm heading this way is HUGE. A very large area will dip below 950 hPa, and the centre may be in the 930's. Wow.

NIL DIFFICILE VOLENTI

Edited by midtskogen - Sunday, 22.12.2013, 19:43 |

| |

| |

| Watsisname | Date: Sunday, 22.12.2013, 21:07 | Message # 96 |

Galaxy Architect

Group: Global Moderators

United States

United States

Messages: 2613

Status: Offline

| I agree, and I didn't find this paper all that powerful for this and other reasons. I think it's an excellent paper for showing how regional climate variations affect a spatially limited dataset, but for the purposes of interpreting the global warming signal it's a bit poor. For that, one really needs to address the effects of variability directly, which some have done.

|

| |

| |

| midtskogen | Date: Wednesday, 25.12.2013, 21:51 | Message # 97 |

Star Engineer

Group: Users

Norway

Norway

Messages: 1674

Status: Offline

| As for the future climate in Europe and the Arctic, I think we're heading into some interesting decades, since the AMO is turning now and the solar activity is falling. Both events, alone, are associated with falling temperatures (though I'm a bit sceptical about the sun link - I do not think it makes an impact in the Arctic). On the other hand it's the first time, at least in human history, that it happens with a 400+ ppm CO2 atmosphere. Even if each of these three things has a fairly big impact on the climate, the combined outcome could be that the climatic change will pretty uneventful for several decades, the least exciting climatic variation for centuries. But such a prediction doesn't make news headlines.

ADDED: A corresponding 30y plot of the NAO is also worth adding. It's showing a higher year to year variation, possibly explaining some abrupt changes in winter temperatures in Europe, but a multidecadal trend seems to be evident even here. While the 1990's had some really warm winters in Scandinavia while more recent years have been approaching normality in agreement with the NAO, the winters around 1920 were surely colder in spite of what the NAO would suggest. Any correlations between NAO, AMO and regional temperatures seem to be quite complex.

Weather:

Added (26.12.2013, 00:51)

---------------------------------------------

I found this discussion between a climate scientist and an economist worth listening through, since both climate science and economy are so much about creating models for a complex reality full of feedbacks which obviously creates some common challenges.

It made me reflect a bit on economics. People have tried to understand macroeconomics for some time in order to make correct models telling us what will happen if this changes, etc, giving us the knowledge of the useful knobs we can use to control economics, not very dissimilar to what climate models also aim to do for global climate. However, after all these years and all this knowledge, we are still unable to prevent major economic crises with or without ample ahead warning. Yet there exists a belief out there that climate science is different. That climate science has got it right. Has tamed chaos and is correctly producing 90+% or whatever probabilities for the outcome of fairly subtle knobs. Of course, it can be true this time. Still, are there not lessons from past attempts to tackle problems of similar nature?

NIL DIFFICILE VOLENTI

Edited by midtskogen - Wednesday, 25.12.2013, 22:53 |

| |

| |

| Watsisname | Date: Friday, 27.12.2013, 02:07 | Message # 98 |

Galaxy Architect

Group: Global Moderators

United States

United States

Messages: 2613

Status: Offline

| There is of course much uncertainty in internal climate variability and sensitivity, but like in economics, uncertainty due to what humanity actually chooses to do is much greater.  There is so much global warming potential in fossil fuels that the degree to which the planet warms largely depends upon on what we do with it. If we continue burning through those resources, we can expect a substantially warmer climate. Or by making critical decisions now, it is still possible to keep warming below 2°C. There is so much global warming potential in fossil fuels that the degree to which the planet warms largely depends upon on what we do with it. If we continue burning through those resources, we can expect a substantially warmer climate. Or by making critical decisions now, it is still possible to keep warming below 2°C.

I also understand that it is easy to think that scientists may be too idealistic or put too much faith in their models, but with my time learning natural sciences and working with people who do theoretical and modelling study, I've seen that they are very conscientious about these things. Just as much effort is put in to understanding the limits of knowledge and quantifying uncertainties as there is in validating models and verifying theory. Climate science is no different. Indeed, just look at chapter 9 of the IPCC reports to see it in action.

|

| |

| |

| midtskogen | Date: Friday, 27.12.2013, 10:51 | Message # 99 |

Star Engineer

Group: Users

Norway

Norway

Messages: 1674

Status: Offline

| Yeah, climate science and economics aren't just trying to model a feedback infested system, but they're both very political.

Let's do a thought experiment. Let's say the IPCC didn't exist. Instead let's suppose an intergovermental panel on economics tasked to write reports on the best economic theories. They warn of major social unrest, mass migration and higher instability due to rising unemployment based on the consensus on economic theories. They describe different taxation scenarios and associated expected unemployment rates. While they do not deny there are uncertainties, they've even put much effort into quantifying it, they strongly insist that immediate action is required. They define a target of 5% unemployment within 2100 compared to 20-30% if current policies are maintained.

What would happen? Would national governments soon adopt their policies? Should we be surprised if many would question the conclusions, methods or even some theories themselves? How should be describe such people?

NIL DIFFICILE VOLENTI

|

| |

| |

| Watsisname | Date: Saturday, 28.12.2013, 06:27 | Message # 100 |

Galaxy Architect

Group: Global Moderators

United States

United States

Messages: 2613

Status: Offline

| How robust is the evidence for what the economists are reporting? And have fundamental predictions of the theory already been verified?

If you are attempting to make an analogue to the present situation with climate science and the decisions currently facing policy makers, then your thought experiment is missing some key details.

|

| |

| |

| midtskogen | Date: Sunday, 29.12.2013, 12:46 | Message # 101 |

Star Engineer

Group: Users

Norway

Norway

Messages: 1674

Status: Offline

| Assume high robustness for the scenarios given, while the social unrest, mass migration stuff is most vigorously upheld by activists. Assume variable robustness for various points, but that it does not change the main conclusions.

But even with an extremely high robustness I think there would be debates.

NIL DIFFICILE VOLENTI

|

| |

| |

| Watsisname | Date: Friday, 03.01.2014, 07:24 | Message # 102 |

Galaxy Architect

Group: Global Moderators

United States

United States

Messages: 2613

Status: Offline

| Yes, I think so, too. There are numerous historical precedents, such as with cigarettes on cancer risk, CFC's on ozone, or tetraethyl lead on public health. Despite robust evidence and scientific consensus of these being serious issues, there was lengthy debate about and against it. Thankfully, the right decisions were eventually made.

It should be pointed out that much of scientific progress depends on skepticism, but it does not benefit so much from debates, especially those outside of academic circles. In cases where the sciences discover something that has implications for society's well being, debate about it can range from helpful to harmful. For climate science I find a great deal of both.

If scientific consensus is that action needs to be taken in order to avoid severe consequences (as you originally specified in your thought experiment), and if this consensus is based on robust evidence, a validated theoretical framework, and fundamental predictions already being confirmed, then I cannot see the wisdom in delaying following the recommended procedures.

|

| |

| |

| Watsisname | Date: Saturday, 04.01.2014, 07:19 | Message # 103 |

Galaxy Architect

Group: Global Moderators

United States

United States

Messages: 2613

Status: Offline

| Back on page one while reviewing the key findings of IPCC AR5 WGI, I noted with some surprise how recent research suggested the feedback from clouds was likely positive. Well today I read a new paper in Nature which not only shows that this result is correct, but also explains the atmospheric physics involved. I’ll go over some of the details, but if you want, just skip ahead to the 4th paragraph where I explain the significance of the results.

The effect of high clouds (above ~8km) is discussed more in other papers, but in short, they have a small positive feedback because the temperature of the cloud tops does not increase much despite a warmer world. This reduces their radiative efficiency even as coverage increases. But low clouds have by far the greatest impact on climate sensitivity because they provide so much coverage and the effect of their albedo is not strongly offset by a greenhouse effect. So if the amount of low clouds increases, this has a cooling effect, as you might expect. The question then is how does cloud coverage change with rising temperature?

With warmer temperatures there is more evaporation (~2% per Kelvin), which implies greater cloud coverage, but a competing effect is that increased tropospheric convection actually dries out the boundary layer. This might seem counterintuitive, but what’s happening is that with more vigorous convection more moisture can be brought out of the thermal without precipitating. This increases the humidity in the upper regions while simultaneously drying out the cloud layer. Global climate models (GCMs) have a lot of variance in simulating these effects and it turns out that this explains about half of the range of values for equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS).

These researchers examined the GCMs for which an ECS value is available and compared to how the models treat the above processes, using an index describing lower tropospheric mixing (LTMI). They found a very robust correlation between these, with high ECS related to greater mixing. This makes sense, as greater mixing causes a positive feedback by drying the boundary layer and reducing clouds. The LTMI index was then compared to observational data via radiosondes and detailed convective models, and it was found that climate models that predict ECS values under 3°C have unrealistically low treatment of tropospheric convective mixing. From this, they conclude that climate sensitivity most likely lies between 3 and 5 degrees Celsius for a doubling of CO2.

I thought this paper was very well done. Many previous studies had suggested that low clouds were responsible for much of climate sensitivity, and others indicated that climate models with higher values of sensitivity also better simulated real atmospheric behavior. But this study is the first to explain a causal mechanism, and support it through observations. I would like to see further work done on this, such as what the researchers suggest by comparing results with models that actually resolve cloud structures. (This might be surprising, but resolving such structures is a very difficult mathematical and computational problem.) The indices for tropospheric convection and comparison to observational data can also be better constrained.

For those interested, here is the paper (sorry, not free to view). I found several media articles on it, but none of them I thought were very good (many are either severely over-hyped or fail to describe what the paper is really about). Reporting Climate Science probably has the best layman's-terms overview.

|

| |

| |

| midtskogen | Date: Saturday, 04.01.2014, 15:15 | Message # 104 |

Star Engineer

Group: Users

Norway

Norway

Messages: 1674

Status: Offline

| Quote Watsisname (  ) If scientific consensus is that action needs to be taken in order to avoid severe consequences (as you originally specified in your thought experiment), and if this consensus is based on robust evidence, a validated theoretical framework, and fundamental predictions already being confirmed, then I cannot see the wisdom in delaying following the recommended procedures.

Real wisdom would be to foresee the nature of the debate or to recognise when talk kills progress, and to let go of one's hobby horses and of one's urge for vindication, and shift focus if there is another target causing less debate yet having the original target as a side effect. In the case of CAGW the focus could shift to making energy cheap and abundant for the entire world. Besides greatly reducing poverty, which is morally impossible to argue against and itself acts like a feedback increasing emissions, a side effect will be reducing CO2 emissions, since fossil fuel clearly cannot provide that kind of energy.

Quote Watsisname (  ) There are numerous historical precedents, such as with cigarettes on cancer risk, CFC's on ozone, or tetraethyl lead on public health. Despite robust evidence and scientific consensus of these being serious issues, there was lengthy debate about and against it. Thankfully, the right decisions were eventually made.

The ozone layer was one of several environmental scares of the 80's and like climate the ozone layer is very difficult to model and is subject to natural variation, but unlike today, political decisions were quickly made. In retrospect one can ask whether some of the arguments were exaggerated. For instance, I remember well the skin cancer scare, which has a truth in it, but it was blown up. That is, there is a link, but other factors like behaviour, protection and place of residence (latitude, altitude) are orders of magnitude more important. The ozone layer depletion couldn't be disputed but was it scientifically correct to attribute it that strongly to CFC? We don't know very much about the natural variation, since there were few observations before CFC entered the scene. One of the exceptions is due to the Norwegian astronomer Sigurd Einbu, but his observations show that during the 40's the ozone layer over Norway was not only slightly thinner than in the 90's, it was also falling at a at a rate of 11.5% per decade, twice or so the rate that justified the CFC ban. While the ban might have been the right decision, it is not entirely clear to me that it was right for the right reasons, and science must be concerned about right reasons rather than right decisions.

It makes we wonder if not the circulation part and regional variations need better understanding. Temperatures vary the most in polar regions. If cloud cover increases here, reflected incoming radiation will not increase much (winter darkness and high albedo in the first place), but it will decrease outward radiation and greatly influence winter temperature. Intuitively, it means that changing wind and pressure patterns are capable of shifting the energy balance even if the global cloud cover does not change.

NIL DIFFICILE VOLENTI

Edited by midtskogen - Saturday, 04.01.2014, 15:48 |

| |

| |

| Watsisname | Date: Saturday, 04.01.2014, 17:59 | Message # 105 |

Galaxy Architect

Group: Global Moderators

United States

United States

Messages: 2613

Status: Offline

| Quote midtskogen (  ) The ozone layer depletion couldn't be disputed but was it scientifically correct to attribute it that strongly to CFC?

Yes, it's called atmospheric chemistry.  The chemical processes by which CFC's and other halogen compounds destroy stratospheric ozone are very well understood, and the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for this work. The chemical processes by which CFC's and other halogen compounds destroy stratospheric ozone are very well understood, and the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for this work.

Quote midtskogen (  ) It makes we wonder if not the circulation part and regional variations need better understanding. Temperatures vary the most in polar regions. If cloud cover increases here, reflected incoming radiation will not increase much (winter darkness and high albedo in the first place), but it will decrease outward radiation and greatly influence winter temperature.

Polar clouds actually have an overall negative feedback. Increase in high-latitude cloud coverage is not efficient at decreasing outgoing thermal radiation, because the surface temperature and cloud top temperature are at similarly cold temperature. Instead the dominant factor is the increase in reflected radiation due to increased optical depth. This effect even outweighs any change in cloud coverage due to poleward migration of jet streams. Of course, at least in the Arctic, the negative cloud feedback is overwhelmed by the positive ice-albedo feedback.

For global cloud feedbacks, low-level low-latitude clouds play the most important role by far. This is not hard to show: half of the surface area of the Earth lies equator-ward of 30° latitude, and the radiative environment here is conducive to giving clouds a strong feedback potential.

If you would like more information, check the references of this paper; I can provide them for you if you need.

Edit: -made a couple changes for discussion flow

Edited by Watsisname - Saturday, 04.01.2014, 18:29 |

| |

| |